Dentists and Sedation

From attracting patients to a dental practice by enabling more relaxing appointments to permitting dentists to comfortably perform long procedures, sedation offers a multitude of benefits to clients and practitioners.

Sedation can help patients fearful of going to the dentist because of anxiety over dental work, discomfort with injections, gagging and prior bad experiences. A 2009 British study indicated 48% of respondents are anxious about visiting the dentist.1 The Journal of Dental Hygiene reported approximately 26% of patients have moderate to severe dental anxiety, and 8% missed a dental appointment because of it.2

Missed appointments can lead to serious dental issues. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stated that, from 2015 to 2018, 25.9% of adults aged 20–44 had untreated dental caries.3

“High-fear dental patients will live with an incredible amount of tooth pain before seeing a dentist,” said Mark Donaldson, BSP, PHARMD, associate principal of Pharmacy Advisory Solutions for Vizient, and a General Dentistry Pharmacology columnist. “We’d like to get them to relax and accept dentistry. Medicines that are safe and effective may need to be used for in-office dental sedation.”

Nitrous Oxide and Minimal Sedation

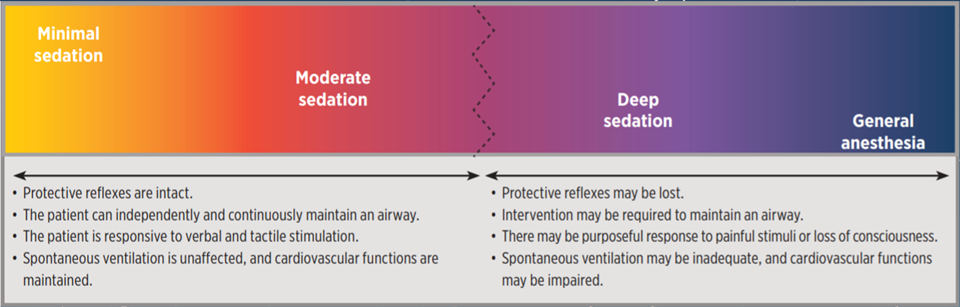

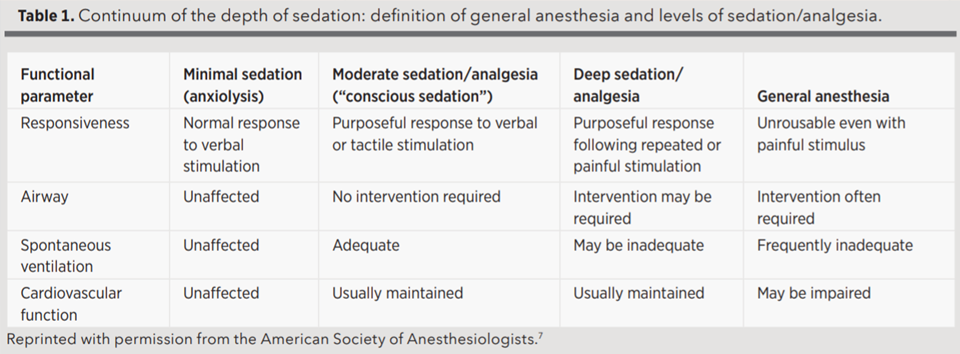

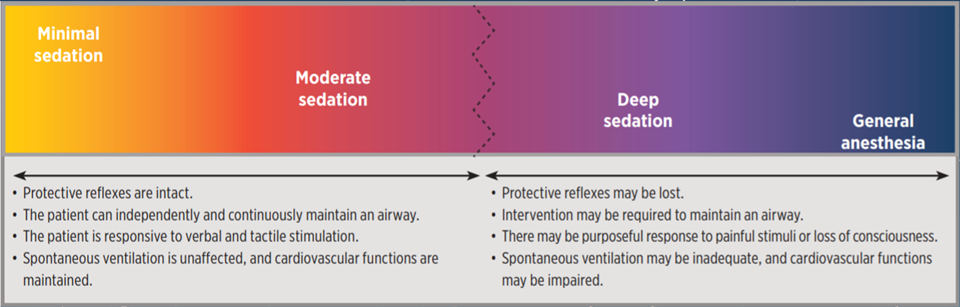

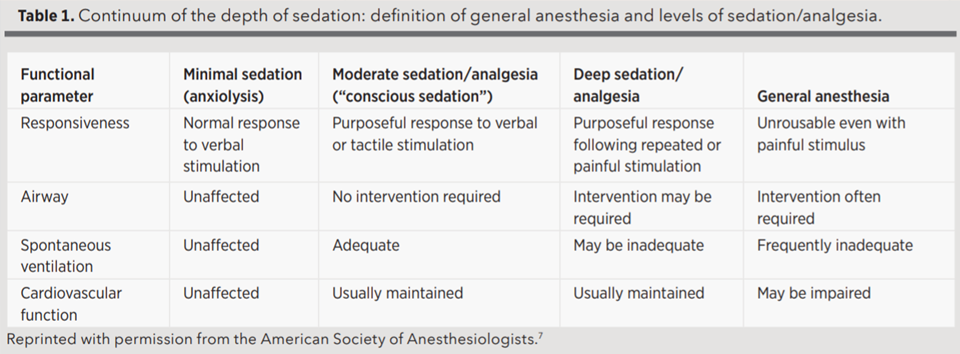

Several types of sedation exist (see Figure). Nitrous oxide, which is inhaled through a small face mask, can relax the patient and decrease procedural anxiety. The patient may feel drowsy during the dental appointment but is clear-headed and able to drive home afterward.

“You could do a short procedure of 15 to 20 minutes or one up to one hour,” said Byron L. Carr, DMD, FAGD, who offers the full range of sedation at his dental practices in Hemet and Temecula, California. “You don’t want them on nitrous oxide for too long, however, as it could lead to an upset stomach in some patients. If the procedure is longer than one hour, you could try oral sedation instead.”

Of the dental practices that offer sedation, 70% use nitrous oxide, according to the American Dental Association (ADA).4 The next level up, minimal (conscious) sedation, involves oral medicine, nitrous oxide or a combination. It is considered safe because the airway is maintained, ventilation and cardiovascular functions are unaffected, and patients can respond normally to verbal commands.5

Scott Dickinson, DMD, in Gulf Breeze, Florida, has patients who request sedation after hearing about it via his radio ads or website. He owns multiple Aspen Dental practices in Florida and Alabama and performs 40 to 60 nitrous oxide sedations per month. One-quarter of these are coupled with oral sedation, with the patient arriving an hour before the procedure in order to be properly sedated and monitored. Minimal sedation covers 95% of his patients that need sedation.

Moderate Sedation

For invasive procedures, Dickinson believes a deeper level of sedation is best. “Most dentists are perfectionists — that is kind of in our DNA. By offering patients sedation, dentists can take the extra time to get it right and not feel rushed. Whether it is a veneer or crown or bridge case where I am preparing six or eight teeth, it’d be a minimum two- to three-hour appointment,” he said. Moderate sedation can be achieved via intravenous (IV) sedation.

Moderate sedation can also be achieved via oral sedation using higher doses of oral medicine than those used for minimal sedation. A patient also could be prescribed a long-acting benzodiazepine to take the night before the dental appointment to help them sleep (e.g., lorazepam or diazepam), then be given a short-acting drug such as triazolam at the dental office on the appointment day to help them relax (the latter is often given at a test appointment first). Nitrous oxide might also be administered.

“When you move up into oral and procedural medicines, the benefits to the patient are relaxation, comfort and potentially no memory of the visit,” said Jason H. Goodchild, DMD, vice president of Clinical Affairs at Premier Dental Products Company and General Dentistry Pharmacology columnist.

But mixing drugs is risky, as it means pushing the envelope. “For moderate sedation and above, the requirements are more stringent, the investment in time for education is more significant and the potential risk is more significant,” said Donaldson.

With moderate sedation, a patient needs to be driven to and from the dental office. The patient can purposefully respond to verbal and tactile stimulation, cardiovascular function tends to be maintained, and no airway intervention is needed. The oral medicines and techniques used require a safety margin wide enough to prevent deeper sedation and an unintended loss of consciousness.5

Patients who need restorative dentistry or orthodontic surgery may need deeper sedation (with a loss of consciousness that results in them not remembering the procedure). With deep sedation, patients respond to painful stimulation but are not easily aroused and may need assistance in maintaining an airway. With general anesthesia, patients cannot be aroused, need assistance maintaining a patent airway and may have impaired cardiovascular function.5 “When you go up the ladder to deep sedation and general anesthesia, it becomes more involved. Should it be done in the office or the hospital? It is all about matching up the ‘rights’ — the right drug, the right dose, the right setting, the right patient, the right education and the right dentist,” said Goodchild.

Deep Sedation and General Anesthesia

Patients who are cognitively impaired, trauma survivors, those with special needs or young children who need extensive dental work are candidates for deep sedation or general anesthesia during dental procedures.

“I’d say the majority of dental anesthesiologists treat pediatric patients. When you get to the point where the patient wants or needs to be completely asleep, they need to seek out a specialist,” said Brian Chanpong, DDS, MSc, a dental anesthesiologist in Vancouver, British Columbia. Dental anesthesiology was recognized as a dental specialty in 2019.

Chanpong owns and operates Anesthesia for Dentistry, a three-room surgical center in Vancouver. His team provides dental anesthesiologists and support staff to dentists who come from their own practices to perform dental surgery on their own patients. They handle 3,000 anesthesiology patients per year, and 90% are pediatric patients, many under the age of 6.

“We call that precooperative age, where the patient does not understand and cannot sit still for long. We don’t want to give them a bad experience at the dentist because it will be long lasting,” he said.

Dental Training for Sedation

Sedation is a skill. Most dental schools train on minimal sedation, and there are postgraduate continuing education courses for moderate sedation. ADA guidelines suggest 16 hours of training for minimal sedation and 60 hours for moderate sedation.8

But there is no national standard. DOCS Education, a provider of sedation training to dentists in North America, launched a website that summarizes state rules for oral sedation (sedation regulations.com). State dental boards may require various permits and recurrent training courses for dentists to provide sedation. “The basic differentiator between minimal, moderate and deep sedation and general anesthesia is potential loss of a patient’s airway. So now you are talking about breathing. The types of training vary a lot as you increase the level and go from oral to IV,” said Goodchild.

Dentists specializing in dental anesthesiology must complete a three-year hospital residency to learn how to properly put patients to sleep and wake them up without complications. For example, propofol is managed at different levels for deep sedation versus general anesthesia. Oral and maxillofacial surgeons also spend a portion of their specialty residency focusing on anesthesiology.

“No U.S. state or Canadian province allows a dentist to receive a permit without having completed a full residency in the hospital. This is for deep sedation and general anesthesia,” said Chanpong. “The response of the patient is what matters.”

Sedation Equipment

Dental offices need to purchase nitrous oxide and oxygen tanks for nitrous oxide administration. To perform oral sedation, they invest in equipment to monitor the patient’s heart rate, pulse, blood pressure and blood oxygen level (using a pulse oximeter). This can cost hundreds or thousands of dollars.

For moderate sedation, dentists also need to purchase sophisticated equipment to monitor electrocardiographic signals and end-tidal CO2 (for oxygen intake levels). “I chose to upgrade because I share the office with an oral surgeon who gives IV sedation (moderate sedation). Otherwise, the oral surgeon would have to bring his own unit,” said Dickinson.

Dentists who offer sedation should examine a patient’s medical history and medication use and obtain informed consent. For minimal and moderate sedation, the dentist and one other staff member must be present and trained in basic life support (BLS), and positive-pressure oxygen should be available.8 An automated external defibrillator (AED) and standard emergency kit are recommended.

A dentist who wishes to offer deep sedation or general anesthesia should have equipment needed for moderate sedation plus resuscitation medications and an AED. The dentist and two staff members trained in BLS must be present.5 The team must also be highly trained in anesthesia and confident enough to handle emergencies.

“I think it is very important for a dentist to stay within their comfort zone. If they are outside of it, nothing good can come. Stay within your training,” said Goodchild.

Increased Revenue

Offering sedation has financial benefits. “If you offer sedation to get patients to relax, not only are they better patients, but you can do better and, in some cases, more dentistry,” said Donaldson.

For nitrous oxide, a dentist may charge no fee, a flat fee or a fee for 15-minute increments. Dentists may charge a fee for oral sedation. The charge is not just for the prescription — it is also for the dentist’s training and experience. Insurance companies may cover part of the cost, or the dentist may be able to list billable services and procedures. When dentists perform longer procedures, it is often on patients who require sedation because they are undergoing costly, extensive dental work. This can also help a dental practice.

“When the young doctors who work with me and my group say they want to grow their practice, the first thing I recommend is that they offer sedation. The big picture is I do more work and see more patients because I offer it,” said Dickinson.

Sarah Louise Klose is a freelance writer based in Chicago. To comment on this article, email impact@agd.org.

References

1. Hill, K.B., et al. “Adult Dental Health Survey 2009: Relationships Between Dental Attendance Patterns, Oral Health Behaviour and the Current Barriers to Dental Care.” British Dental Journal, vol. 214, 2013, pp. 25-32.

2. White, Angela M., et al. “The Prevalence of Dental Anxiety in Dental Practice Settings.” Journal of Dental Hygiene, vol. 91, no. 1, 2017, pp. 30-34.

3. “Oral and Dental Health.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 3 Aug. 2021, cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/dental.htm. Accessed 31 Oct. 2021.

4. “Oral Health Topics: Nitrous Oxide.” American Dental Association, ada.org/resources/research/science-and-research-institute/oral-health-topics/nitrous-oxide. Accessed 31 Oct. 2021.

5. “Guidelines for the Use of Sedation and General Anesthesia by Dentists.” American Dental Association, ada.org/~/media/ADA/Education%20and%20Careers/Files/anesthesia_use_guidelines.pdf. Accessed 31 Oct. 2021.

6. American Society of Anesthesiologists. Continuum of Depth of Sedation: Definition of General Anesthesia and Levels of Sedation/Analgesia, amended 15 Oct. 2014, asahq.org/standards-and-guidelines/continuum-of-depth-of-sedation-definition-of-general-anesthesia-and-levels-of-sedationanalgesia. Accessed 2 May 2019.

7. Goodchild, J.H., A.S. Feck and M.D. Silverman. "Anxiolysis in General Dental Practice." Dentistry Today, vol. 22, no. 3, 2003, pp. 106-111.

8. “Guidelines for Teaching Pain Control and Sedation to Dentists and Dental Students.” American Dental Association, ada.org/~/media/ADA/Education%20and%20Careers/Files/ADA_Sedation_Teaching_Guidelines.pdf?la=en. Accessed 31 Oct. 2021.

Sedation can help patients fearful of going to the dentist because of anxiety over dental work, discomfort with injections, gagging and prior bad experiences. A 2009 British study indicated 48% of respondents are anxious about visiting the dentist.1 The Journal of Dental Hygiene reported approximately 26% of patients have moderate to severe dental anxiety, and 8% missed a dental appointment because of it.2

Missed appointments can lead to serious dental issues. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stated that, from 2015 to 2018, 25.9% of adults aged 20–44 had untreated dental caries.3

“High-fear dental patients will live with an incredible amount of tooth pain before seeing a dentist,” said Mark Donaldson, BSP, PHARMD, associate principal of Pharmacy Advisory Solutions for Vizient, and a General Dentistry Pharmacology columnist. “We’d like to get them to relax and accept dentistry. Medicines that are safe and effective may need to be used for in-office dental sedation.”

Nitrous Oxide and Minimal Sedation

Several types of sedation exist (see Figure). Nitrous oxide, which is inhaled through a small face mask, can relax the patient and decrease procedural anxiety. The patient may feel drowsy during the dental appointment but is clear-headed and able to drive home afterward.

“You could do a short procedure of 15 to 20 minutes or one up to one hour,” said Byron L. Carr, DMD, FAGD, who offers the full range of sedation at his dental practices in Hemet and Temecula, California. “You don’t want them on nitrous oxide for too long, however, as it could lead to an upset stomach in some patients. If the procedure is longer than one hour, you could try oral sedation instead.”

Of the dental practices that offer sedation, 70% use nitrous oxide, according to the American Dental Association (ADA).4 The next level up, minimal (conscious) sedation, involves oral medicine, nitrous oxide or a combination. It is considered safe because the airway is maintained, ventilation and cardiovascular functions are unaffected, and patients can respond normally to verbal commands.5

Scott Dickinson, DMD, in Gulf Breeze, Florida, has patients who request sedation after hearing about it via his radio ads or website. He owns multiple Aspen Dental practices in Florida and Alabama and performs 40 to 60 nitrous oxide sedations per month. One-quarter of these are coupled with oral sedation, with the patient arriving an hour before the procedure in order to be properly sedated and monitored. Minimal sedation covers 95% of his patients that need sedation.

Moderate Sedation

For invasive procedures, Dickinson believes a deeper level of sedation is best. “Most dentists are perfectionists — that is kind of in our DNA. By offering patients sedation, dentists can take the extra time to get it right and not feel rushed. Whether it is a veneer or crown or bridge case where I am preparing six or eight teeth, it’d be a minimum two- to three-hour appointment,” he said. Moderate sedation can be achieved via intravenous (IV) sedation.

Moderate sedation can also be achieved via oral sedation using higher doses of oral medicine than those used for minimal sedation. A patient also could be prescribed a long-acting benzodiazepine to take the night before the dental appointment to help them sleep (e.g., lorazepam or diazepam), then be given a short-acting drug such as triazolam at the dental office on the appointment day to help them relax (the latter is often given at a test appointment first). Nitrous oxide might also be administered.

“When you move up into oral and procedural medicines, the benefits to the patient are relaxation, comfort and potentially no memory of the visit,” said Jason H. Goodchild, DMD, vice president of Clinical Affairs at Premier Dental Products Company and General Dentistry Pharmacology columnist.

But mixing drugs is risky, as it means pushing the envelope. “For moderate sedation and above, the requirements are more stringent, the investment in time for education is more significant and the potential risk is more significant,” said Donaldson.

With moderate sedation, a patient needs to be driven to and from the dental office. The patient can purposefully respond to verbal and tactile stimulation, cardiovascular function tends to be maintained, and no airway intervention is needed. The oral medicines and techniques used require a safety margin wide enough to prevent deeper sedation and an unintended loss of consciousness.5

Patients who need restorative dentistry or orthodontic surgery may need deeper sedation (with a loss of consciousness that results in them not remembering the procedure). With deep sedation, patients respond to painful stimulation but are not easily aroused and may need assistance in maintaining an airway. With general anesthesia, patients cannot be aroused, need assistance maintaining a patent airway and may have impaired cardiovascular function.5 “When you go up the ladder to deep sedation and general anesthesia, it becomes more involved. Should it be done in the office or the hospital? It is all about matching up the ‘rights’ — the right drug, the right dose, the right setting, the right patient, the right education and the right dentist,” said Goodchild.

Deep Sedation and General Anesthesia

Patients who are cognitively impaired, trauma survivors, those with special needs or young children who need extensive dental work are candidates for deep sedation or general anesthesia during dental procedures.

“I’d say the majority of dental anesthesiologists treat pediatric patients. When you get to the point where the patient wants or needs to be completely asleep, they need to seek out a specialist,” said Brian Chanpong, DDS, MSc, a dental anesthesiologist in Vancouver, British Columbia. Dental anesthesiology was recognized as a dental specialty in 2019.

Chanpong owns and operates Anesthesia for Dentistry, a three-room surgical center in Vancouver. His team provides dental anesthesiologists and support staff to dentists who come from their own practices to perform dental surgery on their own patients. They handle 3,000 anesthesiology patients per year, and 90% are pediatric patients, many under the age of 6.

“We call that precooperative age, where the patient does not understand and cannot sit still for long. We don’t want to give them a bad experience at the dentist because it will be long lasting,” he said.

Dental Training for Sedation

Sedation is a skill. Most dental schools train on minimal sedation, and there are postgraduate continuing education courses for moderate sedation. ADA guidelines suggest 16 hours of training for minimal sedation and 60 hours for moderate sedation.8

But there is no national standard. DOCS Education, a provider of sedation training to dentists in North America, launched a website that summarizes state rules for oral sedation (sedation regulations.com). State dental boards may require various permits and recurrent training courses for dentists to provide sedation. “The basic differentiator between minimal, moderate and deep sedation and general anesthesia is potential loss of a patient’s airway. So now you are talking about breathing. The types of training vary a lot as you increase the level and go from oral to IV,” said Goodchild.

Dentists specializing in dental anesthesiology must complete a three-year hospital residency to learn how to properly put patients to sleep and wake them up without complications. For example, propofol is managed at different levels for deep sedation versus general anesthesia. Oral and maxillofacial surgeons also spend a portion of their specialty residency focusing on anesthesiology.

“No U.S. state or Canadian province allows a dentist to receive a permit without having completed a full residency in the hospital. This is for deep sedation and general anesthesia,” said Chanpong. “The response of the patient is what matters.”

Sedation Equipment

Dental offices need to purchase nitrous oxide and oxygen tanks for nitrous oxide administration. To perform oral sedation, they invest in equipment to monitor the patient’s heart rate, pulse, blood pressure and blood oxygen level (using a pulse oximeter). This can cost hundreds or thousands of dollars.

For moderate sedation, dentists also need to purchase sophisticated equipment to monitor electrocardiographic signals and end-tidal CO2 (for oxygen intake levels). “I chose to upgrade because I share the office with an oral surgeon who gives IV sedation (moderate sedation). Otherwise, the oral surgeon would have to bring his own unit,” said Dickinson.

Dentists who offer sedation should examine a patient’s medical history and medication use and obtain informed consent. For minimal and moderate sedation, the dentist and one other staff member must be present and trained in basic life support (BLS), and positive-pressure oxygen should be available.8 An automated external defibrillator (AED) and standard emergency kit are recommended.

A dentist who wishes to offer deep sedation or general anesthesia should have equipment needed for moderate sedation plus resuscitation medications and an AED. The dentist and two staff members trained in BLS must be present.5 The team must also be highly trained in anesthesia and confident enough to handle emergencies.

“I think it is very important for a dentist to stay within their comfort zone. If they are outside of it, nothing good can come. Stay within your training,” said Goodchild.

Increased Revenue

Offering sedation has financial benefits. “If you offer sedation to get patients to relax, not only are they better patients, but you can do better and, in some cases, more dentistry,” said Donaldson.

For nitrous oxide, a dentist may charge no fee, a flat fee or a fee for 15-minute increments. Dentists may charge a fee for oral sedation. The charge is not just for the prescription — it is also for the dentist’s training and experience. Insurance companies may cover part of the cost, or the dentist may be able to list billable services and procedures. When dentists perform longer procedures, it is often on patients who require sedation because they are undergoing costly, extensive dental work. This can also help a dental practice.

“When the young doctors who work with me and my group say they want to grow their practice, the first thing I recommend is that they offer sedation. The big picture is I do more work and see more patients because I offer it,” said Dickinson.

Sarah Louise Klose is a freelance writer based in Chicago. To comment on this article, email impact@agd.org.

References

1. Hill, K.B., et al. “Adult Dental Health Survey 2009: Relationships Between Dental Attendance Patterns, Oral Health Behaviour and the Current Barriers to Dental Care.” British Dental Journal, vol. 214, 2013, pp. 25-32.

2. White, Angela M., et al. “The Prevalence of Dental Anxiety in Dental Practice Settings.” Journal of Dental Hygiene, vol. 91, no. 1, 2017, pp. 30-34.

3. “Oral and Dental Health.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 3 Aug. 2021, cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/dental.htm. Accessed 31 Oct. 2021.

4. “Oral Health Topics: Nitrous Oxide.” American Dental Association, ada.org/resources/research/science-and-research-institute/oral-health-topics/nitrous-oxide. Accessed 31 Oct. 2021.

5. “Guidelines for the Use of Sedation and General Anesthesia by Dentists.” American Dental Association, ada.org/~/media/ADA/Education%20and%20Careers/Files/anesthesia_use_guidelines.pdf. Accessed 31 Oct. 2021.

6. American Society of Anesthesiologists. Continuum of Depth of Sedation: Definition of General Anesthesia and Levels of Sedation/Analgesia, amended 15 Oct. 2014, asahq.org/standards-and-guidelines/continuum-of-depth-of-sedation-definition-of-general-anesthesia-and-levels-of-sedationanalgesia. Accessed 2 May 2019.

7. Goodchild, J.H., A.S. Feck and M.D. Silverman. "Anxiolysis in General Dental Practice." Dentistry Today, vol. 22, no. 3, 2003, pp. 106-111.

8. “Guidelines for Teaching Pain Control and Sedation to Dentists and Dental Students.” American Dental Association, ada.org/~/media/ADA/Education%20and%20Careers/Files/ADA_Sedation_Teaching_Guidelines.pdf?la=en. Accessed 31 Oct. 2021.